- Home

- Robyn Walker

Sergeant Gander

Sergeant Gander Read online

Sergeant Gander

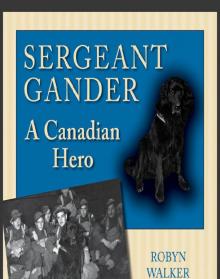

A portrait of Sergeant Gander by artist Anne Mainman.

SERGEANT

GANDER

A Canadian

Hero

ROBYN

WALKER

Copyright © Robyn Walker, 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise (except for brief passages for purposes of review) without the prior permission of Dundurn Press. Permission to photocopy should be requested from Access Copyright.

Editor: Cheryl Hawley

Design: Courtney Horner

Printer: Marquis

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Walker, Robyn, 1969-

Sergeant Gander : a Canadian hero / by Robyn Walker.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-55488-463-6

1. Sergeant Gander (Dog)--Juvenile literature. 2. Canada. Canadian Army. Royal Rifles of Canada--Mascots--Juvenile literature. 3. Dickin Medal-

Juvenile literature. 4. Newfoundland dogs--Juvenile literature. 5. Mascots-

Canada--Biography--Juvenile literature. I. Title.

D810.A65W35 2009 j940.54’251250929 C2009-903265-1

1 2 3 4 5 13 12 11 10 09

We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council for our publishing program. We also acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program and The Association for the Export of Canadian Books, and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishers Tax Credit program, and the Ontario Media Development Corporation.

Care has been taken to trace the ownership of copyright material used in this book. The author and the publisher welcome any information enabling them to rectify any references or credits in subsequent editions.

J. Kirk Howard, President

Printed and bound in Canada. Published by Natural Heritage Books

Printed on recycled paper. A Member of The Dundurn Group

www.dundurn.com

Front Cover Photo:The Royal Rifles with Gander in Vancouver, British Columbia, October 27, 1941. Courtesy of the National

Archives of Canada PA-116791.

Dundurn Press Gazelle Book Services Limited Dundurn Press

3 Church Street, Suite 500 White Cross Mills White Cross Mills

White Cross Mills High Town, Lancaster, England High Town, Lancaster, England

M5E 1M2 M5E 1M2 M5E 1M2

Table of Contents

Acknowledgements

Foreword by Jeremy Swanson

Introduction

List of Maps

Chapter 1 Bear on the Runway

Chapter 2 Sergeant Gander, Royal Rifles of Canada

Chapter 3 Mascot on the Move

Chapter 4 The Calm Before the Storm

Chapter 5 The Battle Rages

Chapter 6 Gander Gets His Medal

Chapter 7 Animals at War

Conclusion

Appendix A List of PDSA Dickin Medal Recipients

Appendix B List of “C” Force Royal Rifles

Appendix C List of “C” Force Killed or Missing in Action

Notes

Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, I must acknowledge the invaluable assistance of Jeremy Swanson, former Commemorations Officer at thesto. He provided a wealth of background information and first-hand accounts about Gander and the veterans themselves, and was unfailing in his willingness to assist in “getting the Gander story out there.” It was never too late or too early to contact him and his replies were always quick and on point. The Gander story is his passion, and as a writer I benefited immensely from his willingness to share.

The assistance of the Hong Kong Veterans’ Commemorative Association (HKVCA) has been immeasurable, with specific thanks to Jim Trick and Derrill Henderson. Their willingness to answer questions and provide resources is much appreciated. The incredible website of the HKVCA is a repository of information about the Battle of Hong Kong that is without equal. Thanks also to Isabel George and Gill Hubbard of the Peoples’ Dispensary for Sick Animals, for their help in obtaining photographs and information about other animal war heroes.

Many thanks to Ron Parker and his fabulous website (dedicated to his father, Major Maurice Parker, Royal Rifles of Canada), which provides a wealth of personal accounts of the battle. Also to Eileen Elms, who was willing to share her childhood memories of “Pal” and of what it was like living in Gander, Newfoundland, back in 1941.

Many, many thanks to all of those individuals who provided photographs and photograph permissions for this book. Their willingness to share has truly enhanced this project.

Much appreciation goes out to Corinna Austin, one of the most talented “undiscovered” writers I know, and my personal muse. The moral support you provide me with on a daily basis means the world.

I would also like to thank my husband and son (Terry and Jed Walker) who supported my writing efforts; Jane Gibson and Barry Penhale at Natural Heritage Books, A Member of the Dundurn Group, for their belief in this project; and Sarah and Samantha, who were there every step of the way.

All possible efforts have been made to trace the copyright holders of the materials used in this book. The responsibility for accuracy rests solely with the author and publisher, and any errors brought to their attention will be rectified in subsequent editions.

Foreword

To say that I was pleased to be asked to write the foreword to this book would be an understatement; it meant so much more to me than the reader could possibly understand. It was a highly satisfying personal honour, due to the extraordinary events that took place when the Gander story came to light.

While I was the commemorations and programs officer at the Canadian War Museum I took on several high-profile projects that resulted in major nationally and internationally recognized events. The Gander project was brought to my desk at the same time as several others, when things were the busiest and most stressful. My two volunteer researchers, Professor Howard Stutt (retired) and Second World War D-Day veteran George Shearman, were already heavily involved in different aspects on several projects at the time. My office and my staff were also actively engaged in the commemorations program to celebrate and mark the fiftieth anniversary of both VE day in May 1995, and VJ day in August 1995.

We were very thin on the ground and there was precious little time or resources to spare for something new. It was an exhausting program for us all, with meetings and events that seemed to happen every second or third day. In the middle of all of that there were research projects for the posthumous award of the Polish Home Army Cross to twenty-six Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) aircrew by the Polish government killed in action over Poland in 1940–45 (1996), and the commemoration of the heroic act of Perth resident Howard Stokes in saving the life of a young Dutch boy in 1945 (1997).

All of those projects would eventually have highly successful outcomes, but at that particular moment their completion seemed impossible. Into the midst of this frantic activity came the dog Gander. He came to my attention in the strangest of ways; many people have since remarked that it seemed to have been pre-ordained. Whatever it was that made it happen, it was certainly at the most appropriate of times.

The Canadian government had introduced the long overdue “Hong Kong” clasp to the CVSM (the Canadian Volunteer Service Medal), a general service medal for veterans of the Hong Kong Battle of December 8 to 25, 1941, on July 2, 1995.

The first presentations of the new bar were made by Veterans Affairs in Ottawa on August 11, 1995, as part of the VJ Day fiftieth anniversary.

At the ceremony I was accompanying the family of Canada’s first Victoria Cross winner, Sergeant Major John Osborn of Winnipeg, who was killed at Hong Kong in the selfless act of saving several of his men by throwing himself on a hand grenade. The family were the guests of the Canadian War Museum as they had donated the medal to the Museum, and I was tasked with looking after them during their stay in Ottawa.

At the social gathering after the medals award ceremony I was gathered with a group of Hong Kong veterans from both the Royal Rifles of Canada and Winnipeg Grenadiers, and the family of John Osborn. We were discussing the medals and the courage of Sergeant Major Osborn. I made a casual remark to the assembled guests that it must have taken tremendous courage and immediate instinctive reaction to have performed such a deed with a deadly smoking hand grenade just feet away, waiting to deliver death and destruction to many.

One of the veterans near me, who I believe was Bob Manchester of the Winnipeg Grenadiers, answered my statement by replying “Yes. Just like that damn dog.” In answer to my immediate question, Bob Manchester and his friend Robert “Flash” Clayton told me all about Gander and what he had done. I shall never forget it; I was stunned by what I heard. I had heard many stories about the battles in Hong Kong, and indeed in many other wars, but never one about a dog picking up a grenade in the middle of battle. That night Manchester told me that he and his comrades had always felt that the dog deserved a medal for what he had done in saving the lives of seven wounded men, but that in the aftermath of war and history no one wanted to know about a dog mascot. Still, they kept hoping it would happen. And so it has.

So that night in August 1995, Gander, the beloved dog mascot of the Royal Rifles of Canada, entered the story and my life. It was the start of three years of dedicated work by my volunteer group and office staff to find out what had happened, research all the evidence, and present the story to the People’s Dispensary for Sick Animals (PDSA) in the United Kingdom for eligibility for the award of the Dickin Medal, known as the “Animals’ Victoria Cross.”

For me, one of the most poignant moments came at the end of August when Roger Cyr, past president of the Hong Kong Veterans’ Association (HKVA), sat in front of me in my office at the War Museum and told me the story of Gander from the point of view of the men who were there and knew him. Roger told the story with difficulty because he had to tell me about the regiment’s battle at the same time. He burst into tears in the middle of it and said to me through his tears, “Jeremy don’t ever let them forget us!” I have always felt that in this meeting, in the moment of tearful memory while he told the story of Gander, he was also telling me the story of the men he served with, and that somehow by recognizing Gander’s bravery perhaps we could all remember the courage of the men who fought, died, and endured unspeakable horrors at Hong Kong, so many years before. It seemed that Gander’s recognition would help the generations that follow to understand and recognize what the soldiers had done.

Roger Cyr was a wise man, as well as a brave one. It would not have been easy to deny a request from a man with such heart and soul. That afternoon I promised him that I would do what he had asked. I did not let him down. It took three years to complete, but we did it. Roger was there at the award ceremony. I am sure I saw a glint in his eye and a wink of thanks as he presented me a life membership in the Hong Kong Veterans’ Association in October 2000, in recognition of my work for Gander and the Association.

What took place between the moment of Gander’s story being revealed and the awarding of the Dickin Medal is contained within this fine book by Robyn Walker. It is a fascinating tale. I have never asked Robyn how she learned of Gander, or why she wanted to do the book, but in meeting with her I did know that it was going to be a good one and that the story would be complete, which it has proved to be. In reading this book I have been immensely gratified to learn so many things about the Gander story that my volunteers and office group did not know at the time. I realize now that there were many “blanks” in the narrative and many unanswered questions over the years, which time and events did not allow us to understand, but now we have them all gathered here, in Robyn’s book.

This is a wonderful story that will ensure that Gander’s story will be remembered in Canadian history for all time. As a result of this book, and Robyn Walker’s impeccable research and hard work, I hope that generations of children will learn about Gander and come face to face with Canadian history, in particular with the history of the veterans of Hong Kong. The late Roger Cyr and Bob Manchester would be pleased. Roger would surely agree that his tearful moment with me, over a decade ago, was worth it for him, his comrades, and for their mascot who has been recognized at last. Let this book, and the story of the brave and wonderful Gander, serve as a literary memorial to them all and a testament to their collective courage. All because of that “damn dog.”

So now we have had the recognition of the veterans and the medal for Gander, and now we have the story in print. I hope to live to see a statue of Gander erected in Ottawa, so that Canadian children and visitors will ask about it, and learn about the extraordinary Canadian men who fought at Hong Kong in extraordinary times. It is a heroic tale indeed.

Jeremy Swanson

Ottawa, Ontario

Introduction

Grenade! A group of Canadian soldiers stare in terror at the small but deadly object that has landed among them. Are the soldiers doomed? Are they destined to die on a dirty, dusty Hong Kong road, thousands of kilometres away from home? Only an act of tremendous courage and selflessness can save the young Canadian soldiers. Suddenly one of their comrades darts forward, ready to make the ultimate sacrifice.

The Battle of Hong Kong

France and Great Britain declared war on Germany on September 3, 1939; the Second World War was formally underway. Under the leadership of Adolf Hitler1, Germany had been steadily overpowering its weaker neighbours, such as Austria and Czechoslovakia, and when Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, both Great Britain and France finally realized that only military intervention might stop Nazi Germany from taking over all of Europe.

However, in the year that followed Germany seemed unstoppable. In April 1940, Norway and Denmark fell to the Germans. On May 10, 1940, the Germans launched a massive attack against the Netherlands and Belgium. In less than a month the Germans had pushed into France, pinning the British Expeditionary Force that had been stationed there against the sea. While many of the British troops were evacuated across the English Channel, France itself surrendered to the Germans on June 22, 1940. Britain now stood alone in Europe against the powerful German forces.

In Asia, Japan was also looking to expand its empire. Japan invaded China in 1937, and in November 1940, signed a pact aligning itself with Germany and

Southeast Asia,

1940.

Italy. This alliance allowed Japan to put pressure on the Dutch (who were under German occupation) to sell more oil to Japan from their East Indian oil reserves.2 Vichy France,3 whose government was, in fact, controlled by the Germans, was pressured into allowing Japanese troops to be stationed in French Indochina. The influx of Japanese troops and aircraft into Indochina posed a very real threat to the British colonies of Burma, Hong Kong, and Malaya, and to the British naval base at Singapore. Britain knew that her Asian colonies were vulnerable to Japanese attack, but most of the British military strength was focused on the war in Europe. Therefore, the British asked Canada to help them defend their colonies in Asia.

The Canadians agreed to help their British ally. Canada had already demonstrated their solidarity with Britain by declaring war on Germany on September 10, 1939, and was already sending a steady stream of war materials and soldiers to support Britain. The Canadian navy patrolled the Atlantic sea lanes, protecting the convoys of supplies being sent from North America, and Canadian pilots and

soldiers were being recruited and trained to help in the fight against Germany. When asked to assist in defending the Hong Kong colony against possible Japanese aggression, Canada agreed to send two infantry battalions to the island to help reinforce the British garrison that was stationed there. During the autumn of 1941, two Canadian units, the Royal Rifles of Canada and the Winnipeg Grenadiers, departed for Hong Kong.

Less than a month after the Canadians’ arrival in Hong Kong, the Japanese launched their attack against the colony. The Canadians fought bravely, but could not withstand the Japanese onslaught and in less than three weeks the colony of Hong Kong was completely overrun. The British and Canadian troops surrendered to the Japanese on Christmas Day 1941, and were dispatched to Japanese prisoner of war camps for the remainder of the war. Those who survived the horrific conditions of the camps and returned to Canada at the end of the war helped to form the Hong Kong Veterans’ Association of Canada. They continue to work hard to preserve the memory of their fallen comrades.

Of all the Canadians who participated in the Battle of Hong Kong, only one was awarded the PDSA Dickin Medal. This medal is awarded to animals that display gallantry and devotion to duty while under the control of any branch of the armed forces. Sergeant Gander is the nineteenth dog ever to receive this medal, and the first Canadian canine to do so. This is his story.

List of Maps

Map:1 Southeast Asia, 1940.

Map 2: Location of Gander in Newfoundland.

Map 3: Territorial boundaries between Canada and Newfoundland, 1941.

Map 4: Japanese expansion in Asia, 1931–41.

Map 5: German expansion in Europe, 1937–42.

Map 6: The Crown Colony of Hong Kong, 1941.

Map 7: The initial disposition of forces in Hong Kong, December 8, 1941.

Sergeant Gander

Sergeant Gander